US Households are in trouble. Almost 40% of Americans have either zero or negative net worth, and most manufacturing jobs have left the country. College graduates are underemployed and stuck with considerable student debt. Unemployment stubbornly hovers near 8%, while the Financial Crisis has decimated the scant financial assets and home equity possessed by the middle class. The Federal Reserve has kept interest rates low but has failed to stimulate vigorous economic activity, prompting some economists to claim we are experiencing a Liquidity Trap.

Yet, something very curious is occurring at the same time: the Dow Jones Industrial Average is reaching record highs almost every week, and large corporations are reporting larger than ever profits quarter after quarter. Annual GDP growth rates above 2% indicate the economy should be back in good shape... CEO pay is at an all-time high, and big banks are bigger than ever.

Isn't this all supposed to "trickle down" somehow? Or is this another kind of "liquidity trap?"

GDP and National Income

Yet, something very curious is occurring at the same time: the Dow Jones Industrial Average is reaching record highs almost every week, and large corporations are reporting larger than ever profits quarter after quarter. Annual GDP growth rates above 2% indicate the economy should be back in good shape... CEO pay is at an all-time high, and big banks are bigger than ever.

Isn't this all supposed to "trickle down" somehow? Or is this another kind of "liquidity trap?"

GDP and National Income

GDP is an expression in US dollars of the total value of goods and services produced and is frequently cited by economists as an indicator of a country's economic condition. We've talked before about GDP, which is for the purposes of this article what you can think of as the total revenue of the United States each year (this isn't totally accurate, view a proper definition here).

Of course, revenue is just a raw amount of funds incoming. In almost every business, the largest percent of revenue goes to paying worker wages/salaries.

National Income (in the sense that the Federal Reserve uses it) is an accounting of earnings paid out. There are several categories; worker wages, proprietor's income, interest paid and corporate profits -- among others.

In 2012, for example, the GDP of the United States was roughly $15.7 trillion, while the National Income totaled $13.8 trillion (88% of GDP). This is normal. Since 1945, National Income has ranged between 87% and 90.6% of GDP. After all, the entire point of business is to get paid, right?

But a closer examination reveals precisely whom is being paid.

As we can see, worker wages as a percent of National Income are currently at their lowest point since 1951. The best period in terms of worker wages seems to be from 1969-1983. Afterward, we see rather large changes from decade to decade, never quite recovering from a sudden drop in 1984. For the last sixteen years worker wages as a percent of National Income never equaled even the lowest measure of wages from the period of 1969-1983.

Proprietors' Income is a raw amount of income paid to the owners of businesses that are not corporations. These are plumbers, electricians, corner groceries, boutiques, law offices, medical practices-- small businesses and other business endeavors that are not incorporated. Some of these may be LLC's (Limited Liability Companies) or LLP's (Limited Liability Partnerships) these may also include individual owners of popular corporate endeavors, such as a McDonald's Restaurants franchise. Proprietors' businesses are usually taxed through the individual, which means that their business revenues are viewed as income, usually regardless of most other factors. This can mean a proprietor can be subject to a much higher tax rate than is necessary.

When politicians talk about "job creators," they really should try to be more careful about who they really mean-- Proprietors employ the majority of Americans in the Private Sector (even though the largest single employers are large corporations like Wal-Mart), and they generally pay them better than their corporate counterparts. This is the most common type of business structure in the US.

Let's look at a graph of Proprietors' Income over the same time period as the previous graph (1946-2012):

Proprietors' Income is a raw amount of income paid to the owners of businesses that are not corporations. These are plumbers, electricians, corner groceries, boutiques, law offices, medical practices-- small businesses and other business endeavors that are not incorporated. Some of these may be LLC's (Limited Liability Companies) or LLP's (Limited Liability Partnerships) these may also include individual owners of popular corporate endeavors, such as a McDonald's Restaurants franchise. Proprietors' businesses are usually taxed through the individual, which means that their business revenues are viewed as income, usually regardless of most other factors. This can mean a proprietor can be subject to a much higher tax rate than is necessary.

When politicians talk about "job creators," they really should try to be more careful about who they really mean-- Proprietors employ the majority of Americans in the Private Sector (even though the largest single employers are large corporations like Wal-Mart), and they generally pay them better than their corporate counterparts. This is the most common type of business structure in the US.

Let's look at a graph of Proprietors' Income over the same time period as the previous graph (1946-2012):

|

| Proprietors' Income as a percent of National Income peaked in or before 1946, reaching an all-time low in 1982. The recovery has been tepid at best. |

So if workers' wages and proprietors' income have fallen as a percent of National Income- yet National Income keeps rising- whose income payments have increased?

Corporate profits (after taxes) in 2012 are the highest they've ever been-- both in numerical amount and as a percent of National Income. Workers are being paid less and small businesses are being crowded out of the marketplace. Meanwhile, the tax burden on individuals (mostly through payroll taxes) has increased as a percent of Federal tax revenue, with corporations supplying a smaller and smaller portion of tax revenue since the 1950's.

How can this be? Aren't they making more money than ever? Didn't we just show that? Yes. Yes, they are making more money than ever. But they are also paying a lower effective tax rate.

Quick explanation: When you pay your individual income taxes, you are taxed not on your total amount of income, but on a portion that is left over after you claim certain deductions from your gross earnings. The amount you pay after all deductions and other tax credits compared to your total gross income is your effective tax rate. For example, if you qualify for a bunch of standard tax deductions and tax credits, your total gross income may be $52,000, but you're actually taxed on a significantly smaller amount. While your tax bracket may require you to pay a 25% tax rate, your effective tax rate may be as low as 18% or 19% (or lower, depending on how tricky your accountant is).

Corporations have a much sweeter deal to begin with than individuals: they are only taxed on their profits. They can deduct almost all expenses of business operations and maintenance -- including employee wages, building rents, energy costs and R&D (Research and Development). They can also write off losses as deductions on future tax returns going forward seven years. Through lobbying and other forms of influence upon the legislature, corporations have been able to secure many additional tax credits and deductions, along with only being taxed on their domestic profits to begin with. Profits made overseas are not taxable and can be held off-shore indefinitely.

Imagine if you could deduct the full cost of feeding, clothing, sheltering and otherwise maintaining yourself and your family-- and still had more deductions and tax credits you could take! Fantastic, right? I mean, how much would you ultimately pay in taxes? I can tell you that if I could deduct all my living expenses from my total gross income, my taxable income would be like $3.50. Here you go, Federal government-- here's my thirty-five cents.

Just to fully illustrate the point, here's a graph depicting Corporate Profits (before tax) as a percent of National Income:

It doesn't look much different than the after tax figures, does it?

|

| Corporate profits as a % of National Income (AFTER taxes) |

Income and Assets of US Households/Individuals

Now here's something that does not seem to get counted in the Federal Reserve's accounting of National Income: full employee compensation. As a quick example, I can tell you that the current chairman and CEO of JP Morgan Chase, Jamie Dimon, is paid a yearly salary of $1 million, with bonuses of up to $5 million (imagine getting a bonus that was 500% of your salary)... but his total yearly compensation through stock options and other payments in 2012 was closer to $42 million-- his total yearly compensation last year was almost forty-two times his salary!

This puts Mr. Dimon in a situation unique from most Americans. 90% of his compensation is made of liquid assets. This translates most of his total compensation directly to wealth. He does not pay a dime in taxes on stock options until he decides to sell them. Then, he is only taxed on the amount that he gained from the point that he acquired them (Capital Gains). It's a tricky tax avoidance that is perfectly legal, but it really punctuates the difference in how the Top 1% amasses wealth versus the strategy of the "average" American.

The point of this section is not to create divisions between classes. I'm pointing out income and wealth disparity as a means to bringing the majority in this country together. A "popular" criticism of the Occupy Wall Street movement was that it was a bunch of unemployed dirty hippie communists who were jealous of "successful" people and wanted to rob them of the fruits of their labor. This critique is not only patently incorrect, it is myopic and willfully ignorant. Still, in a supposed "meritocracy" such as the US, presenting the idea that some people are taking more than they truly deserve is actually pretty insulting for those who feel they've really worked hard at being financially successful.

The reality of the situation is that in the fullest, truest evaluation of the economy in the United States it is the consumer-- the workers, the common folk-- who drive the economy. We buy all of the goods and services, we provide the labor, we pay the majority of taxes to the government, we fund the entire nation and all the corporations and small businesses, we create and sustain the national economy. Well, ninety-eight or ninety-nine percent of us do it, anyway.

In terms of being "job creators," the consumer majority of the US takes the cake as well. The bottom 90% of income earners spends between 70% and 100% (sometimes through the magic of credit, they spend more than 100%) of their income directly back into the economy, while the top income earners spend progressively smaller and smaller percentages of theirs back into the economy. Even when observed as an important part of the investment structure, top income earners rarely make investments that aren't profitable for themselves in the short or medium term. Why would they? Isn't the whole point of investing to turn a profit?

The bottom 90% of workers take home an estimated 53.5% of all wages, while the "Next 9%" take home about 24% of all wages. Together, 99% of Americans are taking home around 78% of wage earnings and most if not all of it gets put directly into the consumer economy creating more jobs and more demand.

Income Class Demographics:

How large is the disparity between average rates of pay in these categories? Well, the most significant divisions occur in the upper percentiles. In other words, the difference between the income and wealth of the Working Poor and the Upper Middle Class is actually much narrower than the differences between the Upper Middle Class and the Top 1% of income earners-- and the differences between incomes of persons in the Top 1% are especially marked.

|

| Average yearly income of Americans, 2011, by specified brackets. The inset portion is represented in a different scale so that the average income of the bottom 90% is visible. |

It's a good idea to make the distinction between wealth and income at this point. Income, in the sense that I am speaking about it here (it's different for tax purposes), is total compensation (either monetary or through liquid assets like stock options, etc.) for employment or services rendered. Wealth (or we can talk of Net Worth) is the total amount of assets owned by an individual or business minus their liabilities/debts.

US Households & Non-Profits "collectively" own over $76 trillion in assets. Households have approximately $13 trillion in debts/liabilities ... so we can say the Net Worth of US Households is about $63 trillion. That sounds like a very stable economy, right?

...Except that those assets are mostly owned by the top income earners and the debts/liabilities are mostly owed by the bottom 80%-90%.

|

| Go to "Who Rules America?" For more information. |

Here are some graphs created by Prof. G. William Domhoff at his website "Who Rules America?" depicting wealth and debt by specific types of assets (2010).

First, by Investment (Financial) Assets:

|

| Source: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html |

...and then by other types of assets:

|

| Source: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html |

As we can see, the bottom 90% owns a scant amount of investment assets and chiefly holds "other types" of assets-- home, life insurance, pension accounts, etc. The bottom 90% also holds 73% of the debt.

For additional demographic breakdown, we can refer to these G. William Domhoff pie charts:

|

| Source: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html |

When there is a significant economic crisis, the wealthy may have major losses, but it is usually the poor who are hardest hit. Here are more graphs from G. William Domhoff depicting median income, net worth and financial wealth from before and after the Financial Crisis:

|

| Source: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html |

|

| Source: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html ,Wolff (2012). |

Household Debt, Income and Net Worth

The Federal Reserve lumps Households and Non-Profits into one big bundle. I suppose this makes sense, since Non-Profits don't fit into any of the usual business categories and Non-Profits do not make a significant percentage of assets or liabilities in the grand scheme. Henceforth, I will mostly drop the term "Non-Profits" and refer to the entire group only as "US Households."

One way we can evaluate the fiscal situation of US Households is by applying a simple equation or two to the data available to us.

Liquidity Ratio - The total dollar amount of assets divided by the total amount of debts/liabilities.

Debt Ratio - The total dollar amount of debt/liabilities divided by the dollar amount in assets.

Here is a chart of the Liquidity Ratio of US Households & Non-Profits, 1945-2012:

We can see that the Liquidity Ratio generally fell over this time period, losing most ground during the 1950's. I don't have information that would break this down into more useful bits-- for example, determining who exactly was "leaking" liquidity. A general clue, however, is that beginning in the 1950's there were massive amounts of new homes being built and it became a more "normal" expectation of Americans to own their own home. Currently, national home ownership rates are close to 66%. However, the full value of these homes do not count as assets until the mortgage is completely paid off, so especially in the first decade of a 30-year mortgage, you may see a large reduction in your own Liquidity Ratio.

I do have more information for 2010, however, and have created a snapshot of Liquidity Ratios for three different income groups:

Here also are graphical depictions of US Households & Non-Profits Debt Ratio.

...here is the Income Class snapshot of 2010 Debt Ratios:

On its own, these aren't damning pieces of evidence- after all, a high liquidity ratio? Isn't that what it means to be rich in the first place?

...And a Debt Ratio below 0.5 (50%) is not that bad, anyway (bottom 90%).

Actually, when banks look at debt ratios while considering making a loan to a business or individual, they use a different metric: Debt-to-Income Ratio (debt divided by pre-tax income). So let's look at median household income in the US.

The Median Income is not the average income, it is the numerical center of a list of all incomes. It is usually presented as a measure of the overall state of personal finances because as the center rises, it is assumed that the average condition has improved.

Median Income is as defined here:

The actual "Median Income Per Individual" in the US is currently around $36,000. However, Median Income often refers to a "Household Income" which may represent more than one income earner, as long as these two earners share residence. Many, if not most, US households include more than one income earner. The household Median Income (as of 2011) is $50,054.

We will look at the household rates, because the rest of the data from the US Census and the Federal Reserve is by household, not by individuals.

Here is a graph I created using data from the Federal Reserve which depicts Median Income vs. Average Household Debt 1967-2012:

In the above graph, we can see that the fluctuation in median income (the blue line) has been minimal- about 19% since 1967- while the amount of debt held per household (the red line) has increased to 386% of Median Income during the same period.

As we can see, the average debt per household in the US was closely correlated to the Median Income until around 1983 or 1984. Afterward, the Median Income failed to grow in step with the amount of home loan financing and other credit extended to the general public.

We have already discussed the fact that most households do not own assets that are easily liquidated such as stocks, bonds and other fund accounts. Their main asset (and usually also their main liability) is their home.

By using a Debt-to-Income Ratio (total debt divided by income) instead of looking at debt divided by total assets, we can see that the average debt-to-income ratio is 2.13 (or 213%). Banks consider a consumer over-extended if this ratio is above 0.3 (30%).

GDP growth compared to growth of Median Income from 1967-2011:

The above graph shows that while GDP per Household has increased, Median Income has barely seen any increase at all. As noted above, the median income of Americans is an indicator of overall wages-- which according to the National Income figures, are depressed. We have seen that corporations continue to make record profits while paying less and less in taxes. What about the bottom ranks of income earners? What is their financial situation? After all, they are the ones who will require the most government support through Medicare, Medicaid and Food Stamps.

| Table 1: Income, net worth, and financial worth in the U.S. by percentile, |

| Wealth or income class | Mean household income | Mean household net worth | Mean household financial (non-home) wealth |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top 1 percent | $1,318,200 | $16,439,400 | $15,171,600 |

| Top 20 percent | $226,200 | $2,061,600 | $1,719,800 |

| 60th-80th percentile | $72,000 | $216,900 | $100,700 |

| 40th-60th percentile | $41,700 | $61,000 | $12,200 |

| Bottom 40 percent | $17,300 | -$10,600 | -$14,800 |

| From Wolff (2012); only mean figures are available, not medians. Note that income and wealth are separate measures; so, for example, the top 1% of income-earners is not exactly the same group of people as the top 1% of wealth-holders, although there is considerable overlap. SOURCE: http://www2.ucsc.edu/whorulesamerica/power/wealth.html |

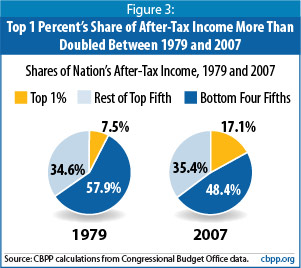

Where are the income gains going? If productivity per household is at an all-time high, and National Income keeps rising, who is making all the gains? Not the average American.

All of the individual income gains have been going to the Top 1% of wage earners. This is a long-term trend, as shown by the above graphic by The New York Times.

Once again, the poorest are hit the hardest in this wage stagnation-- here is a chart by the University of Oregon on Minimum Wage since 1938, adjusted for inflation. The blue line shows the nominal amount, and the Red points are the inflation adjusted amounts:

More and more Americans are under-employed: working part-time or for (near) minimum wage. As some of my "favorite" Republican pundits say, "In this 'Obama Economy' [sic] the only new jobs are minimum wage!"

We can hardly blame this on Obama, or even Bush for that matter-- After a close examination of this data, it is clear that fundamental changes to our economy occurred in the early 1980's and have accelerated over time.

1. There was an unwieldy abundance of increasingly cheap credit following the high interest rates of the late 70's and early 80's. This trend has continued to the current year, allowing the vast majority of Americans to become over-extended with debt.

2. Labor unions were dismantled and/or circumvented.

3. The tax structure was completely rewritten. The idea was that if the wealthy can keep more of their money, they will use it to invest in the Private Sector and improve the economy ("Trickle-Down Economics").

|

| There is no correlation between the Top-Marginal tax rate and economic growth, despite what some politicians tell us. |

5. A brand of economic thought dubbed "Neo-Liberal Economics" helped carry "Supply-side" economics (also referred to as Reaganomics) into the political arena. This also happened to some extent at the same time in the United Kingdom. It has largely been a failure for everyone except the very rich, as jobs that used to be filled by skilled workers in manufacturing have been shipped overseas to be done much more cheaply in developing nations. Businesses that manufacture products domestically generally can't compete, and workers who once had well-paying jobs in manufacturing were laid-off and left to find lower-paying jobs in unrelated fields.

6. Corporate executives began receiving salaries that are much higher than the historical average. Many CEO's of top corporate enterprises now make over 350 times the salary of their average employee-- not the janitor or the mail-boy-- the average employee. Compare that to the 1980 figure-- when CEO's made only 42 times the pay of the average worker.

Golden Years?

All of this was good for economic growth, right? Isn't the GDP larger than ever?

Yes, the GDP grows every year unless there is a recession. So barring recessions, the GDP will rise to record numbers practically every year, and each year the same percent increase in GDP is a slightly larger nominal increase (for example, 3% of $12 trillion is $360 billion, but 3% of $15 trillion is $450 billion). It's mostly relevant to look at GDP in terms of percent increases/decreases, since the raw dollar amounts become less significant over longer time periods.

I'm going to ask you to look at GDP over the last 90 or so years in a rather un-traditional way. Normally, we talk about GDP as a dollar amount based on data collected by quarters and then averaged together by year-- so that we can ignore seasonal disruptions in the market and concentrate on year-to-year comparisons. How about we apply that same method to decades? What does GDP growth look like when we view average GDP growth rates by decade?

This graph interprets GDP in Nominal amounts (or the current year's dollar amount-- what it was actually recorded as in that year). The graph is read from right to left, with 1921-1930 on the far right, and the most recent data on the far left. We can see the unparalleled government spending of WWII reflected in the large spike on the right, and an accelerated post-war economy heading into an impressive economic expansion during the 1970's.

It is clear that since peaking at growth rates averaging over 10% (which is really an unsustainable growth rate in any economy) we have seen steady declines in growth until reaching the 2000's. Still, in nominal amounts, the growth rate continues to look healthy. Most economists agree that a GDP growth rate of 2% to 3% is a "healthy" state for an economy. But this view completely ignores inflation.

Inflation isn't merely the injection of physical currency into the economy-- nobody counts how many dollar bills there are in the world before pricing their goods and services (that would be pretty mean, anyway)-- it is actually an index of rising prices that leads to a weakening of the buying power of the dollar (deflation would be the opposite: falling prices that lead to a strengthening of a dollar's buying power). See: CPI.

Here is the same analysis applied to GDP which is inflation adjusted to 2011 dollars:

It now looks like the Great Depression had better GDP growth than this last decade! Well, that's not really true. The Great Depression had many wide swings of GDP growth and contraction that just averages out to a deceptively healthy-looking rate, and when you couple that with Depression-era deflation (increased buying power of the dollar), you get this distortion. World War II GDP still looks extreme, and now the biggest post-war expansion looks like it occurred from 1961-1970. The 1970's look rather weak... and that's because of the extremely high inflation rates of the 1970's. The 70's were doubly bad because of very high interest rates (see the back-story on the Financial Crisis). However, when inflation rates and interest rates sharply fell in the 1980's, it led to a rebound in the economy, fueled by consumer borrowing. "Supply-siders" and neo-liberal economists loved it.

Banking institutions came up with lots of new loans, people who always wanted to own a home suddenly could afford to do it, and paying by credit card quickly became popular and widely accepted. More and more people were heading to college and today over $1 trillion of consumer credit debt comes from student loan debt.

When the Cold War ended, there were teams of computer scientists and mathematicians- formerly developing missile programs for the Pentagon- who needed some new jobs and this happened to coincide with a fantastic idea that Wall Street was having just at that moment: fancy new financial instruments. Please see my previous post on the Economic Collapse for more information on what Wall Street did.

Another particular concern is the shifting of asset ownership over the last 50 or 60 years. In the following pie charts, "Corporate Non-Financial Business" represents companies like Disney, McDonald's, IBM, and Johnson & Johnson- corporations that produce things but whose primary function is not financial instruments; "Non-Corporate Non-Financial Business" represents the non-incorporated businesses aforementioned while discussing proprietors' income; "Households and Non-Profits" represent (by-and-large) private individuals of ALL income classes (and an insignificant amount of assets held by non-profit companies & charities); "Financial Business" represents banking institutions, investment operations, all of "Wall Street," and most insurance brokers/providers.

|

| In 1945, Households owned almost half of all assets, and the remaining assets were almost evenly split between the three remaining categories. |

In the Post-Reagan era (1989-Present), the Federal Reserve has had the same monetary policy- keep interest rates low and encourage borrowing. It seemed to have revitalized the economy and led to a stable growth pattern. But did it really?

I have spent a lot of time talking about the policy decisions that have supported this change, and the trends in economic thought and business tactics of large/powerful corporate interests-- but much of this change was facilitated also by consumer behavior. While I'm likely to return to this subject in the future, I'd like to recommend this lengthy documentary on the subject-- "The Century of the Self". Please watch it when you have a great deal of time. It is actually about four hours long.

If it turns out the video has been removed after you follow the link, here is an embedded video of the introduction to the piece, so you get a gist of what it's about at least:

Meritocracy or Plutocracy?

It is thoroughly rational for all businesses to seek maximum profits and minimum taxation. It is equally rational to offer generous compensation packages to CEO's and to underpay most other workers, as this will maximize profitability. Take any advantage you can get-- it's a tough world. Lobbying, off-shore accounts in tax shelters, outsourcing entire departments to "third-world" nations: it all makes perfect sense in a profit-driven economy. It all may be rational and legal, but is it ethical?

Growing up in the 1980's as the youngest child of a pair of Baby Boomers, I was taught that if I went to college and worked hard enough, I was guaranteed to have a modicum of financial success. I would grow up, get a well-paying job, get married and buy a house. The American Dream, as it were, is to go through this progression. The sky is the limit. Our free market capitalism would ensure that if I was intelligent, hard working and had some ingenuity, I could even become very wealthy.

The reality of this situation is that I was born 30 years too late. We no longer live in that kind of economy. Sure, I can still have all of those things; a college diploma, a wife and family, a car, a house-- but only if my wife works full-time as well, and if we're willing to go into debt up to 200% of our combined income.

If I wish to have the same level of success that my father did, it doesn't really matter how hard I work or whether or not I'm intelligent-- all that seems to matter is if I can get hired as a top executive in a Fortune 500 company or come up with the newest internet sensation. Otherwise, the best I can hope for is to be in the shrinking middle class where I will be taxed to silly proportions, while my boss makes 350 times my salary and pays a lower effective tax rate than my kid who works part-time at Sbarro's.

If I find work with the right company at the right time, and they happen to offer full health and dental benefits I can be relatively sure that no surprise health problem will catapult my family to homelessness and/or poverty... as long as they don't suddenly outsource my department to some emerging market in Indonesia. In that case, I'll be lucky to come out of the bankruptcy proceedings with even the shirt on my back.

Finding a job as an older person is tough. It's likely you will never find one again that has as good a package as your last job. Your years of experience don't make you more qualified; instead, they make you less likely to be employed. There are millions of fresh college grads every year who will gladly do the same job for 1/2 the pay rate and without being guaranteed a benefits package or 401(k).

Opening your own business is very risky and tricky-- you'd be lucky if you can compete with the larger corporate conglomerates and keep your doors open for more than a year-- even in a small town.

Is the "American Dream" really only about possession of whatever trendy electronic gizmo, fashion accessory or McMansion we can acquire? Is it totally necessary for each of us to own a house and two cars? What are we sacrificing for that?

Worse, what kind of an economic system are we perpetuating by participating in this kind of circus? What effect does this have on the rest of the world?

...And what message does this send to our children?

Afterthoughts:

When I wrote this post, I sent a copy to my sister to review. I asked if the ending sounded "whiny" or entitled, if it came off as being incendiary and divisive. My sister told me she liked the personal touch and that it was valid to have these thoughts and feelings about the "new economy."

But the above section isn't exactly how I feel. I don't really care that I will never be as "successful" as my parents' generation (what does that even mean?). I'm not a materialistic person who needs possessions to demarcate my self-worth. What I really need is to feel freedom-- freedom from hunger, freedom from sickness, freedom from debt.

Psychological studies have shown that once the basic needs of an individual are met - food, shelter, healthcare - no additional amount of material goods will provide more sustainable happiness... and they're right.

I feel fulfilled when I get to express my creativity and work for (sometimes hard-won) goals that exercise both my intellect and my values. I need to have time to spend with my loved ones and the ability to set my own goals and achieve them. I don't feel that the economy we have created in the last 30 years allows us all to do that. I don't think that we will live in a truly "free" society until it does.

What I resent about our current economy is the constant threat to our more basic needs, and the way that we are increasingly limited from providing for our own basic needs without participating in a specific way with the economy.

Let's face it-- we are the luckiest population of people who ever lived in the history of the planet in terms of abundance. We Americans all have access to all the food, material comfort, toys and entertainment that we could ever need or desire. We have unparalleled luxury and automated systems to do much of the unpleasant work. Our grandparents (or great-grandparents) lived through the Great Depression. Our trivial worries mean nothing to them.

But society tells us we always need more. We need a bigger house, a fancier car, a fast boat... we need vacations in tropical destinations and designer clothes with prominent labels so everyone knows how much money we spent to look that nice.

We need an advanced degree in a specialized field that affords us a high salary and medical benefits (otherwise we don't truly deserve either) and in order to attain all of these things we must participate in the credit system.

If we fail in the credit system, it affects every aspect of our basic survival needs. We could lose our home and our transportation, which could lead to us losing our jobs, which could lead to us losing our healthcare insurance and/or retirement benefits, which could cause us to be further indebted. The biggest fear is that we'll wind up friendless, homeless and hungry like the people we all try to ignore while we're on our way to work.

In order to avoid this potential cataclysm, we give up certain things-- time with our loved ones, we give up some sleep (not that important, is it?), we skip meals or put off going to the toilet in the interest of being "more productive," we often sacrifice our health-- we even sometimes sacrifice our self-respect or our need to be creative and spontaneous. It's all to keep ourselves plugged in to a system that will always demand more.

The worst part is that this economic system is fundamentally unstable. We could lose everything (as individuals and as a society) even if we do it all "by the book."

I think we should change that, and while I have mentioned certain things that can be done in previous posts, I will write more about this in the near future.

However, there is a maddeningly simple solution: Stop wanting things. Stop being a consumer and start being a person. We don't need big houses, fancy cars, slick mobile smartphones, impressive job titles or any other of the silly status symbols that "society" tells us we must have to prove that we're somebody. Just reject it. Ignore the big corporate box stores and shop at the locally-owned businesses in your area. Get involved in local government and keep your community safe from Wal-Mart and their ilk (by voting against zoning changes or vote for large tax increases on those businesses)-- make it unprofitable for them to stay in your area. Bank at a local cooperative bank. Join a farm-share. Support local everything.

We can build our own economy. We can build our own future.

We can do so much better.

Notes on the data:

I went to many different sources to get the preceding information, but mostly all the data came from the Federal Reserve, US Census, IRS, the Bureau of Economic Analysis and the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Much of the data doesn't seem coherent until it's plugged into a spreadsheet and some graphs are made.

Limitations of the data:

I don't have access to all the information I would need to give a completely precise accounting of the financial situation of American citizens. I can give a fairly accurate portrayal of the current standings for the general population, but without information on specific persons or detailed info on groups in different income classes, I cannot be as precise as I had hoped at the beginning. The source information is intentionally aggregated in such a way as to protect individuals' privacy and as a result some numbers are skewed, mostly because there is no demographic breakdown; a few billionaires can sway the information in a big way. However, an overview of fiscal position is still possible, and for one particular year-- 2010-- I have additional information that was helpful in this way.

I don't have access to all the information I would need to give a completely precise accounting of the financial situation of American citizens. I can give a fairly accurate portrayal of the current standings for the general population, but without information on specific persons or detailed info on groups in different income classes, I cannot be as precise as I had hoped at the beginning. The source information is intentionally aggregated in such a way as to protect individuals' privacy and as a result some numbers are skewed, mostly because there is no demographic breakdown; a few billionaires can sway the information in a big way. However, an overview of fiscal position is still possible, and for one particular year-- 2010-- I have additional information that was helpful in this way.

_1950_-_2010.jpg)